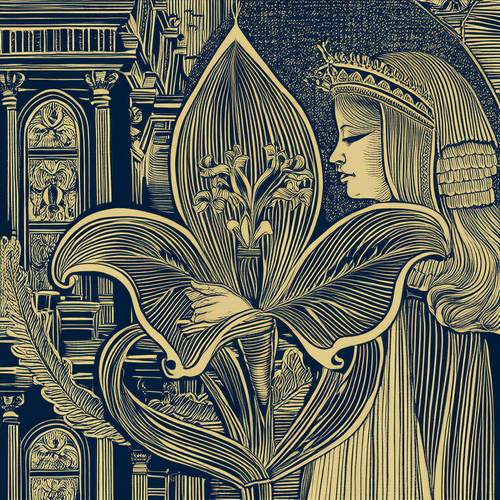

The royal courts of Europe have long been fascinated by symbols and hidden meanings, but few motifs carry as much intrigue as the fleur-de-lis of the French monarchy. This stylized lily, often associated with purity and divine right, conceals a lesser-known dimension—what scholars of heraldry now call "The Butterfly Code" of the Valois and Bourbon dynasties. Recent discoveries in archival manuscripts suggest that the fleur-de-lis was not merely a static emblem but a dynamic cipher, its curves and flourishes designed to mimic the wings of a butterfly, a creature laden with esoteric significance in Renaissance occultism.

At the heart of this theory lies a peculiar manuscript from the library of King Charles V, unearthed in 2019 beneath a palimpsest of tax records. The vellum pages reveal meticulous sketches of fleurs-de-lis superimposed over the anatomical drawings of swallowtail butterflies, accompanied by marginalia in Occitan. These notes, deciphered by cryptolinguists at the Sorbonne, reference a "flight of souls" and "the metamorphosis of kings." The connection seems deliberate: the three petals of the fleur-de-lis mirror the wingspan of certain Lepidoptera, while the central stem aligns with the insect's thorax. Was this a mere artistic whim, or did the French crown embed a deeper biological allegory into its heraldry?

The butterfly's lifecycle—from caterpillar to chrysalis to winged adult—resonated profoundly with medieval notions of resurrection and royal legitimacy. Dr. Élodie Lefèvre, a historian specializing in Renaissance symbology, argues that the fleur-de-lis's "hidden wings" served as a visual promise of dynastic renewal. "When Louis XII adopted the crowned butterfly as his personal emblem alongside the fleur-de-lis in 1499, he wasn’t merely decorating tapestries," she explains. "He was asserting that the Valois line, like a butterfly, could shed its mortal constraints and emerge transcendent." This symbolism reached its zenith under Francis I, whose artisans at Fontainebleau embedded butterfly silhouettes into the masonry of the Galerie François Ier—each positioned to catch the light at solstice dawn, casting fleur-de-lis shadows on the floor.

Yet the most compelling evidence emerges from the 1594 coronation of Henry IV. A previously overlooked inventory from the Abbey of Saint-Denis describes the king’s mantle as embroidered with "golden lilies that flutter when the wind doth lift the cloth." Microscopic analysis of surviving fragments conducted in 2022 confirmed the presence of iridescent beetle wings stitched beneath the fleurs-de-lis—a technique borrowed from Mesoamerican art, likely via Catherine de' Medici’s workshops. When worn in procession, the mantle would have created a shimmering illusion of movement, transforming the static heraldic symbol into a living, breathing entity. This theatrical flourish aligns with contemporary accounts describing Henry’s coronation as "the moment when the garden took flight."

The Butterfly Code’s influence extended beyond visual propaganda. Musicologists studying the court ballets of Louis XIII have identified a recurring melodic motif—a rising minor third followed by a trill—referred to in compositions as "la volute des ailes" (the spiral of wings). This phrase appears in scores whenever dancers bearing fleur-de-lis motifs performed turns mimicking a butterfly’s erratic flight path. Even the famous Louvre labyrinth, destroyed in 1668, allegedly contained hedges trimmed into fleur-de-lis shapes that, when viewed from the upper windows, resolved into a swarm of butterflies during certain times of day.

Why has this connection remained obscured for centuries? Part of the answer lies in the French Revolution’s systematic destruction of royal symbology. But as Dr. Jean-Claude Thierry of the Collège de France notes, "The ancien régime’s greatest secrets weren’t hidden in vaults—they were displayed in plain sight, disguised as decoration." Recent advances in spectral imaging have revealed preliminary sketches beneath portraits of Marie de' Medici, showing her initially holding a butterfly net instead of a scepter—a detail painted over at Richelieu’s insistence. Such discoveries suggest that the Butterfly Code was an open secret among the elite, a visual language asserting that divine right monarchy wasn’t just inherited; it underwent periodic metamorphosis.

As research continues, scholars debate whether this phenomenon was uniquely French or part of a broader European trend. The Habsburg double eagle, for instance, exhibits similar entomological influences in its wing segmentation. But what sets the French case apart is the deliberate interplay between fixed heraldry and fluid biology—a tension that perhaps reflects the monarchy’s struggle to balance tradition with reinvention. The fleur-de-lis, that most rigid of symbols, may have always contained within its gilded lines the promise of wings.

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025

By /May 21, 2025