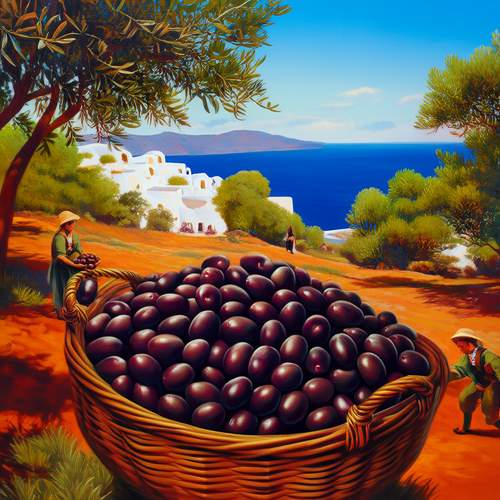

The coastal city of Kalamata, nestled in the southern Peloponnese region of Greece, is renowned for producing some of the world’s finest olives. Among the many characteristics that define Kalamata olives, their acidity level stands out as a critical factor influencing both flavor and quality. Unlike mass-produced table olives, Kalamata olives undergo a unique fermentation process that results in a distinctively rich, tangy profile. The interplay between natural growing conditions, traditional harvesting methods, and meticulous curing techniques contributes to their signature acidity, making them a staple in Mediterranean cuisine and beyond.

What sets Kalamata olives apart is their protected designation of origin (PDO) status, which ensures that only olives grown in the Messinia region can bear the name. The region’s microclimate—hot, dry summers and mild winters—combined with mineral-rich soil, creates an ideal environment for olive cultivation. The Koroneiki and Kalamon olive varieties, primarily used for oil and table consumption respectively, thrive here. While acidity is often associated with olive oil, it plays an equally vital role in table olives. The lactic acid produced during fermentation not only preserves the olives but also enhances their complex, slightly wine-like tartness.

The journey from tree to table is a delicate balance of art and science. Kalamata olives are typically hand-harvested in late autumn to prevent bruising, which can lead to undesirable fermentation. Once collected, they are slit or cracked to allow the bitter oleuropein compound to leach out before being submerged in brine. This brine, often enhanced with red wine vinegar or lemon juice, kickstarts lactic acid fermentation. Over several weeks, sugars in the olives convert to lactic acid, lowering the pH and creating that characteristic sharpness. Unlike Spanish or California olives treated with lye for rapid curing, Kalamata olives rely on slow fermentation, which preserves nuanced flavors and a firmer texture.

Acidity in Kalamata olives isn’t just about taste—it’s a marker of quality and authenticity. The European Union’s PDO regulations stipulate that authentic Kalamata olives must have a pH below 4.3, ensuring sufficient acidity for both safety and flavor. Artisanal producers often achieve even lower pH levels (around 3.8–4.0), resulting in a more pronounced tang. This acidity also acts as a natural preservative, allowing the olives to maintain their quality without artificial additives. When shopping for Kalamata olives, consumers should look for a vibrant purple-black hue and glossy skin—signs of proper fermentation—while avoiding overly soft or dull-looking specimens, which may indicate poor acidity control.

Beyond their culinary appeal, the acidity of Kalamata olives has health implications. Lactic acid, a byproduct of fermentation, promotes gut health by supporting probiotic bacteria. The olives’ low pH also means they retain higher levels of polyphenols—antioxidants linked to reduced inflammation and heart disease risk. However, their bold flavor means they’re often packed in brine or olive oil, so sodium content can be a consideration for some diets. Chefs worldwide prize Kalamata olives for their ability to cut through rich dishes; a handful can elevate a simple Greek salad, pasta puttanesca, or even a modern fusion dish with their unmistakable brightness.

Climate change poses emerging challenges for Kalamata’s olive growers. Rising temperatures and unpredictable rainfall patterns may alter the acidity and oil content of olives, potentially affecting their PDO status. Some producers are experimenting with adjusted fermentation times or organic acid supplements to maintain consistency, though purists argue this deviates from tradition. Meanwhile, counterfeit "Kalamata-style" olives—often made with inferior varieties and artificial acidification—flood international markets, undermining the genuine article. For now, though, the true Kalamata olive remains a testament to how acidity, when nurtured through centuries-old methods, can define a culinary treasure.

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025

By /May 26, 2025